|

|

Location: GUIs >

Windows >

Windows in 1983

Microsoft Windows

by Phil Lemmons The desktop metaphor and the mouse present attractive concepts, but Apple's Lisa or IBM's PC XT running Visi On exceeds the budget of the average personal computer user. Both of these systems require a hard disk and great quantities of RAM (random-access read/write memory). Although the mouse itself is a small part of the expense, it is a symbol of this approach to software, and some computer users have been heard to mutter, "What price mice?" Another factor keeping down the mouse population has been the shortage of things for them to point at (or the shortage of application software). Until there is a large installed base of Lisa and Visi On systems, many software authors will forgo the expense of developing applications programs for these systems. Prospective buyers of personal computers, on the other hand, are unlikely to buy a Lisa or Visi On until more software is available. Apple's own software for Lisa is magnificent, but other applications programs are only now emerging. Visicorp is making a major effort to induce programmers to write more for Visi On, but the requirements of a Unix development system is an obstacle to the smaller software houses and independent designers. The expense underlying the Unix development system is the hardware required to run it - once again, lots of memory and a hard disk. This keeps most of us staring a the MS-DOS or CP/M command line and hoping that a sudden fall in the prices of RAM and hard disk will open the way to metaphors and mice. With the introduction of Microsoft Windows, however, the company that brought us MS-DOS promises a mouse-and-window show running off two 320K-byte floppy disks and 192K bytes of RAM. (More RAM is required, of course, with each additional application.) To make Microsoft Windows even more attractive to personal computer users, Microsoft promises to price Windows "as an operating-system component" - that is, inexpensively. The economics of Microsoft Windows will also appeal to programmers. Programmers don't need to buy special hardware or to learn Unix in order to develop software that runs under Microsoft Windows - they can user their own IBM Personal Computers. Moreover, programmers can take advantage of the ability to customize windows so that each software house retains its own distinct look within the Microsoft environment. The same enlightened attitude enabled Microsoft to resist the temptation to reserve Windows as an environment for its own applications programs. Microsoft is making Windows available to a number of applications software houses, including some major competitors. Microsoft Windows is an installable device driver under MS-DOS 2.0 using

ordinary MS-DOS files. Complete compatibility with MS-DOS means that Windows

will at least let you run any application that runs under MS-DOS. In the

worst case, Windows will turn the fill display over to an MS-DOS application

and return you to your place in Windows. "Language bindings" will enable

programmers to write software for Microsoft Windows in any Microsoft programming

language.

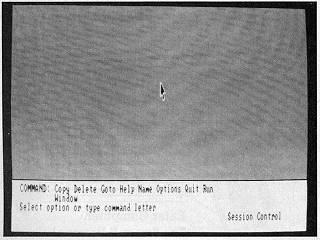

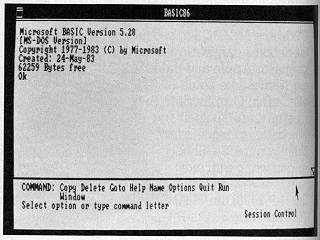

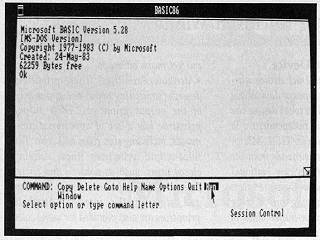

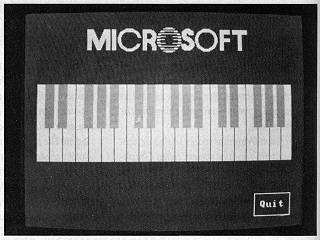

Running Microsoft Windows Photos 1-13 show a sequence of operations in Microsoft Windows. The photos on pages 52-53 show a variety of machines whose manufactures have adopted Microsoft Windows as an applications environment. During normal use, Microsoft Windows displays one or more windows, each with a different application. You can move the cursor from one windows to another. You can move windows, change their size, scroll, get help appropriate to the context in which you are working, and transfer data among windows. Windows determines the highest level of data transfer mutually acceptable to the two applications, with plain ASCII (American National Standard Code for Information Interchange) as the last resort. The "session-control layer" becomes the equivalent of the empty desktop where you can manipulate files. The available commands appear near the bottom of the screen. Normally, Microsoft Windows will restore the desktop to the state at the time of its last use. In photo 1, we start from scratch. To see the available applications programs, you either use the mouse to position the cursor on the command "Run" or type the letter "R." Windows lists all the applications programs as commands, and you point at the desired program and click the mouse to run it. You could also type the appropriate letter instead. In photo 2, BASIC 86 is running in a large window extending the full width of the desktop. Because BASIC 86 does all its input/output through MS-DOS, it can run in a Window. Microsoft calls such software "co-operative." The bottom of the screen shows the commands available in the session-contol layer. You can use the session-contol layer to run another program in parallel with BASIC 86. The first step toward running a program is shown in photo 3, where the cursor points at "Run." Microsoft Windows will now display a list of the programs available. Photo 4 shows the next application selected. In this case, the program that's run is "uncooperative" - that is, it doesn't do everything through MS-DOS system calls, sometimes going beyond the operating system to write directly to the hardware addresses such as those of screen memory. Microsoft Windows can't run such a program in a windows and must give it the entire screen. That is why photo 4 does not show the session control layer beneath the display of "Piano." |